“Art as Catharsis” by Naomi Prefferman, Senior Writer , The Jewish Journal. 1995

Six weeks ago, The Jewish Journal visited the acclaimed, nationally touring exhibit, “Witness & Legacy: Contemporary Art about the Holocaust,” showing through, May 13 at the Finegood Art Gallery of the Valley Alliance of the Jewish Federation of Greater Los Angeles. Danuta Rothchild’s “Silence” series hearken back to Polish childhood, when she felt virtually “overfed” on stories of the Holocaust. The artist’s mother barley escaped the Nazis; and at school and summer camp there were all-too-frequent visits to crematoria and screenings of gruesome documentary films.

“It was overwhelming,” says the 44-year-old painter, who simultaneously had to hide her Jewish identity from anti-Semitic teachers and classmates. So for years, Rothschild did not touch the Holocaust on canvas, as she studied at the prestigious Academy of Arts in Warsaw, immigrated to the States in 1971 and set up a studio in Westlake.

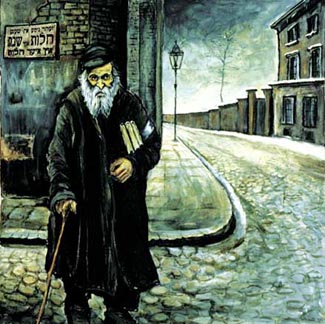

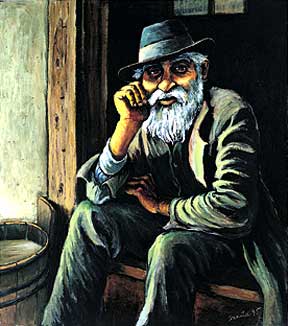

Instead, she painted survivors of other cultures, from Native Americans to “homeless, forgotten children.” Tackling the Jewish genocide, she now reflects, “would have been too painful.”

The change came in the early ’90s, when Rothschild’s Native American pieces were selected for a show on the various genocides of the world. “But the artists dealing with the Jewish Holocaust had no clue,” Rothschild said. “What was missing, for me, was the pain, the silence of the [Shoah]. That was when I decided I had to approach the subject.”

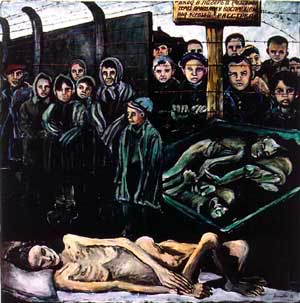

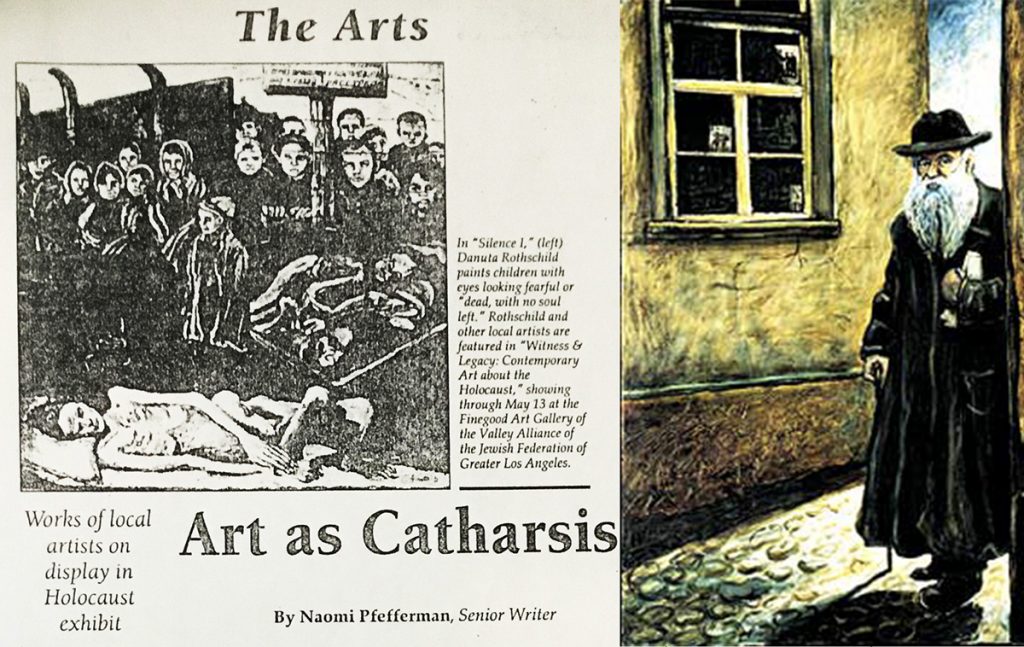

For “Silence I,” the artist recalled a childhood visit to Maidenek, where she wandered among shoes, toys and suitcases of murdered children. In her seven-by-seven foot, expressionist painting, ghostly children stare from behind barbed wire, above a skeletal mother figure in cadaverous blues and greens. Their eyes are fearful or “dead, with no soul left, ” while in the center of the painting – hovering all too near -is a sepulcher containing emaciated corpses.

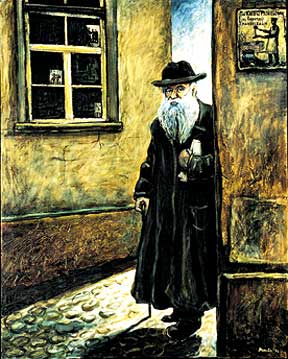

In “Silence II,” Rothschild eulogizes her grandfather, who endured Danuta. The yellowed painting depicts frightened bony men standing nude and helpless in barracks. In the “Silence” pieces, Rothschild tries to capture the feelings of the victims, and the task took an emotional toll. “It was one of the most painful experiences in my life,” she recalls. “I could only work on the paintings for a couple of hours at a time, and then I had to walk away.”

ln fact, the pieces were considered so disturbing that they were pulled from one exhibit after they allegedly upset visitors. But Rothschild wants viewers to feel upset, in a world where the strong still prey upon the weak.